On August 24th, the Japanese government began discharging treated wastewater into the sea from the Fukushima nuclear plant, which had been destroyed by a tsunami 12 years ago.

Japan has carefully addressed the situation by subjecting the liquid to a sophisticated filtration and dilution process. While the water still contains a potentially harmful radionuclide called tritium, experts believe its levels are too low to be a concern.

Japan aims to release over a million tonnes of this water in the next 30 years, a plan supported by many scientists and the UN’s International Atomic Energy Agency.

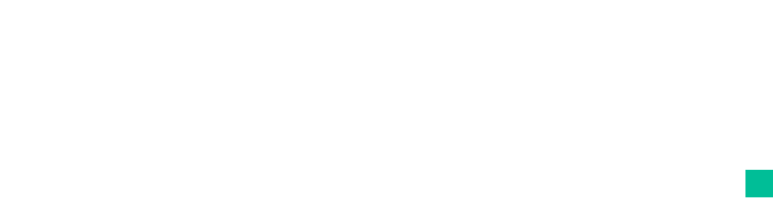

However, China has strongly criticized Japan’s actions, labeling them as reckless. In response, the government halted imports of Japanese seafood.

While the state media extensively reported on the story, they scarcely mentioned the scientists in favor of the plan. Nationalist online users amplified the narrative with baseless allegations about tainted fish and health hazards, urging a boycott of Japanese products.

In certain Chinese cities, there’s been a rush to purchase salt, with long queues forming. Some residents believe salt might be contaminated or help in treating radiation sickness, though it doesn’t.

Certainly, some scientists and environmental activists stand against Japan’s plan. They argue that further research is essential to understand the potential consequences.

Additionally, there is skepticism about trusting Japanese authorities, especially since the Fukushima disaster revealed concerning degrees of governmental corruption, incompetence, and deceit.

Yet, China’s reaction might be more rooted in political dynamics than other factors. Historical grievances against Japan remain strong in the nation. Chinese nationalists frequently reference Japan’s aggressive actions during the 1930s and 1940s.

A previous disagreement concerning five islets in the East China Sea even spurred war rhetoric.

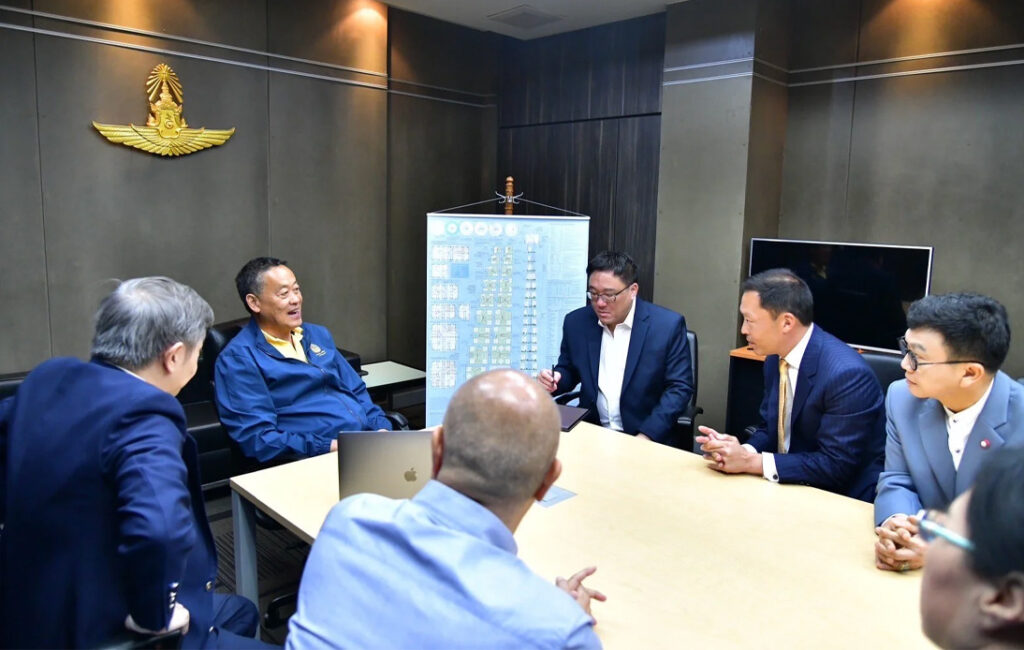

Lately, Beijing’s officials have observed, not without concern, Japan’s growing ties with America and its enhanced backing for Taiwan, an island which China considers its own.

Regarding the wastewater topic, Japan claims China has declined opportunities for discussions to clarify concerns.

Another significant conference has further complicated the situations. On August 18th, US President Joe Biden welcomed Japan’s leader, Kishida Fumio, and South Korea’s head, Yoon Suk-yeol, for a unique gathering.

Historically, tensions have strained the relationship between Japan and South Korea. Yet, China’s growing influence has nudged them towards unity.

However, China might now see a chance to sow discord between them. While South Korea’s government backs Japan’s wastewater approach, the Korean opposition and a large portion of its citizens oppose it – some Japanese also remain split on the matter.

For China, this wastewater discharge has emerged at a suitable moment. Their economy is grappling with challenges, and every week seems to introduce an additional set of disappointing data.

Japan’s measures have served as a diversion from this bleak scenario. Nonetheless, economic anxieties might undercut China’s stance.

China is the leading buyer of Japanese seafood, and limiting these imports might adversely affect Chinese businesses nearly as much as Japanese fishermen. Such a restriction could be temporary.